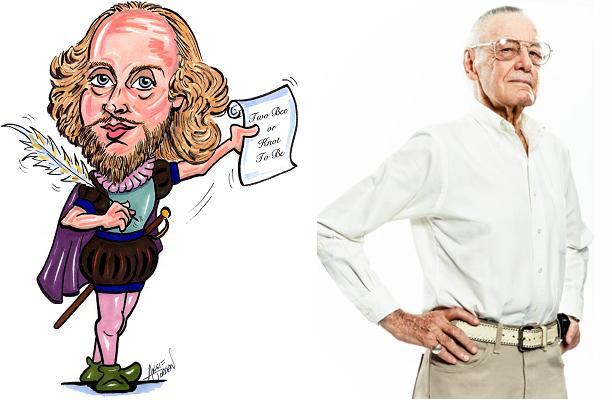

Why Comics Are as Important as Shakespeare

People who write for a living routinely credit heavyweights like Faulkner, Hemingway and Proust with showing them the way. In my case much of the credit goes to comic books.

Between 5th and 11th grade, I read almost nothing else. Instead of trashing ''The Flash,'' ''Green Lantern'' and ''The Fantastic Four,'' my English teacher nudged me toward books that bore no resemblance to ''Silas Marner'' or that deadly dull ''Heart of Darkness.'' Comics and fantasy paved the way for science-fiction novels like ''The War of the Worlds'' and ''Fahrenheit 451'' and eventually for mythology, most notably the ''Iliad.''

Homer was bloody and fantastical, to be sure. But the essence of his story -- the scheming gods dressed up as humans, the epic journey to Troy and the clash of Titans in the field -- came as no surprise to me. It had been thoroughly laid out in a classic line of comics that was readily available at the corner store.

The notion that young Americans can access the Western cultural heritage only through a defined set of serious books -- known as ''the canon'' -- is wrong on its face. Pop culture has been so thoroughly infused with allegedly ''classic'' themes that you can glean them from pulp novels and movies.

Purists argue that children need to read the great books in the original. But from a pedagogical standpoint, what matters most is that they engage whatever they read early and deeply enough to make reading, thinking and writing second nature. Whether it is ''literature'' or ''trash'' makes little difference.

This simple principle was lost in this month's canon wars in San Francisco, where two members of the board of education claimed they could lower black and Latino drop-out rates, and improve test scores, by requiring that 70 percent of the books read in high school come from non-white authors. Beaten back by cries of ''literary apartheid,'' the board dropped the percentages but required that teachers use at least some works by authors that ''reflect the diversity of culture, race and class'' of San Francisco, whose students are almost 90 percent minority.

Escalating the factionalism, the gay and lesbian contingent persuaded the board to order that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender writers be ''appropriately'' identified when their books were used in class. To this faction, a writer's race and sexual preference seem to matter as much as his or her words.

High school students argued vigorously for the resolution, describing books by dead white men as a most grievous hardship. But under existing school policy, they were allowed to choose many of the books they read for class. Of the 10 books required each year, four are specified by the teacher and three are chosen by students and teachers from a recommended list that already has plenty of non-white writers. The students themselves choose the final three, from wherever they wish.

So if students missed out on minority writers, it was probably because they were not choosing them, or because they were not reading beyond what was needed for English class. The problem begins at home, where most of them grow up without books and alienated from reading. Researchers tell us that those who master reading by third grade -- and become independent readers by fourth -- generally do fine. The others lose so much ground that by high school it is too late to help them.

Instead of squandering influence in the canon wars, San Francisco's board should be blitzing minority neighborhoods, making sure that young parents read to their children and get books into their children's hands before first grade.

The diversity impulse is generally good. The notion that our common cultural heritage is locked up in musty old classics that people praise but rarely read is almost comically absurd. But San Francisco shows both how the diversity impulse can be oversold and how mightily traditionalists belly-ache when the books they claim to have read in school are forced to give way even a little bit.

The debate about the difference between ''trash'' and ''literature'' is fine for cocktail parties. But where children grow up cut off from books, the only relevant question is how to get them to read, write and think. The answer is to start early and to use whatever works.

Source Site:

http://www.nytimes.com/1998/03/29/opinion/editorial-observer-why-comics-are-as-important-as-shakespeare.html?pagewanted=1

|

2

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

DCF

3/11/2010

DISCLAIMER: This posting was submitted by a user of the site not from Earth's Mightiest editorial staff. All users have acknowledged and agreed that the submission of their content is in compliance with our Terms of Use. For removal of copyrighted material, please contact us HERE.