Are Superheroes Anti-democratic?

The American Prospect says that politically-themed comic storylines such as Marvel's Civil War collapse under the weight of their own contradictions.

The cover story of The American Prospect's November issue, entitled "The Revolt of the Comic Books," appears at first glance to report objectively how post-9/11 comic books have been gunning--sometimes literally--for the Bush White House. In fact, freelance writer JULIAN SANCHEZ posits that the liberal or civil libertarian allegories built into storylines about preemptive war, warrantless surveillance and more serve only to highlight how ill-equipped the present illustrated universe is to tackle real current events, especially using inherently neoconservative icons such as superheroes.

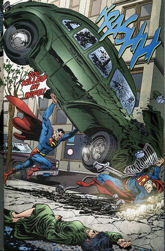

To illustrate (no pun intended) his point, Sanchez uses some of the biggest "event" storylines assembled by Marvel and DC Comics in recent years, with the closest scrutiny falling on Civil War. Marvel's '06-'07 crossover epic centered upon the "Superhuman Registration Act," which required costumed heroes to be licensed and trained by the U.S. government. This act divided the heroes and set them into devastating conflict, with the dissident side condemning the trade of liberty for security.

To illustrate (no pun intended) his point, Sanchez uses some of the biggest "event" storylines assembled by Marvel and DC Comics in recent years, with the closest scrutiny falling on Civil War. Marvel's '06-'07 crossover epic centered upon the "Superhuman Registration Act," which required costumed heroes to be licensed and trained by the U.S. government. This act divided the heroes and set them into devastating conflict, with the dissident side condemning the trade of liberty for security.

"Their civil libertarian arguments turn out to

hold very little water in the fictional context," Sanchez states. "The 'liberty' the act infringes is the right of well-meaning masked vigilantes, many wielding incredible destructive power, to operate unaccountably, outside the law--a right no sane society recognizes."

In the writer's analysis, when Captain America insists that heroes must be "above" politics, he is claiming that "messy democratic deliberation can only hamper the good guys' efforts to protect America."

However, Sanchez admits that the difficulties in making such a conceit work can be blamed primarily on the requirements of the superhero genre, in which total power must be completely benign, and in which problems arise because "the wrong people--supervillains--sometimes get powers." So, according to him, comics creators are making more attempts at social themes through "maxi-series" like DC's Infinite Crisis, which emphasizes how evil occasionally is formed from good, but misguided, intentions, by pitting heroes against each other.

However, Sanchez admits that the difficulties in making such a conceit work can be blamed primarily on the requirements of the superhero genre, in which total power must be completely benign, and in which problems arise because "the wrong people--supervillains--sometimes get powers." So, according to him, comics creators are making more attempts at social themes through "maxi-series" like DC's Infinite Crisis, which emphasizes how evil occasionally is formed from good, but misguided, intentions, by pitting heroes against each other.

After all, Sanchez writes, "superheroes don't form [Political Action Committees]; they have slugfests, because the narrative of the superheroic redeemer demands that more prosaic means of conflict resolution--diplomacy, say--prove ineffectual."

The conclusion is that an effective political allegory cannot succeed in such a context, and that comics writers--liberal or conservative--must first invent "a grammar and a vocabulary for a new sort of superhero narrative--one capable of telling us that, sometimes, great power comes with the responsibility to not use it."

In the online comments section following the article, several readers had dissenting opinions. Addressing the failure of Civil War as a political message, JOSH G. states that the purpose of the registration act is too ambiguous ("SuperHUMAN" or "SuperHERO"?) for the writers' intended message to be clear, while NGAH suggests that the act may simply be an allegory for "the power of any citizen to keep elected officials in line."

CODE NAME D, however, believes that Sanchez has missed the point of genre fiction by interpreting Civil War to have a political agenda when the SRA is only "an excuse to pit superheroes against each other in mindless combat."

"Let's face it," writes LOW-TECH CYCLIST, "superheroes are inherently antidemocratic."