''Fangs'' For The Memories, Forry

Forrest J Ackerman died on Thursday, December 4th. Does that mean anything to you? It should.

"The sad part is that mainstream media doesn't seem to care about Forrest J Ackerman," lamented SyFy Portal's MICHAEL HINMAN the day after the 92 year-old's passing. "Why should mainstream media care? It's because Ackerman was a primary contributor to making science-fiction something that could be defined and understood by the masses."

Unfortunately, Hinman's first statement appears to be true: since Ackerman's heart gave out on him at home in Los Angeles five days ago, two news briefs have popped up in this writer's RSS feed, only one of which could be considered "mainstream" media. It's tragic, because science fiction and horror fandom would not be what they are today if not for "Uncle Forry."

A native of L.A., in "Karloffornia," as he called it, Forrest James Ackerman met his destiny at a "Horrorwood" drug store in 1926 when he purchased an early issue of Hugo Gernsback's "scientifiction" magazine Amazing Stories. In the next three years, Forry won a San Francisco Chronicle contest for his story about a trip to Mars, and founded The Boys Scientifiction Club.

"I would have included girls," he said once, "but at that time female fans were as rare as unicorns' horns."

Forry's groupings did eventually include females such as future screenwriter Leigh Brackett, whose final writing credit would be The Empire Strikes Back. She was part of Clifton's Cafeteria Science Fiction Club, as was legend-in-the-making Robert A. Heinlein (Starship Troopers). It was to this group that Ackerman introduced a promising young writer named Ray Bradbury.

"He changed my life," Bradbury once said. The prolific author of Fahrenheit 451 and The Illustrated Man never produced a truer statement. In 1938, Ackerman published Bradbury's first short story in Imagination!, the fan publication of the Science Fiction Society. The very next year, Forry bankrolled Ray's own fanzine, Futuria Fantasia.

It was during this same period that Ackerman met and befriended another future genre giant. At the 1938 re-release of King Kong, Ray Harryhausen -- who would go on to become the king of stop motion animation effects -- was impressed enough with a display of movie memorabilia to seek out the owner.

The assortment which caught Harryhausen's eye was merely the seed of what would grow into a great oak -- nay, a forest. Ackerman's repository of movie stills, props and masks, books, posters, paintings and other items developed into what has been called the largest personal collection of genre memorabilia in the world. An estimated 300,000 artifacts once filled Forry's "Ackermansion," the 18-room Los Feliz home he shared with his "life companion," wife Wendayne, the college professor and translator of French and German science fiction novels who wondered why, in 1951, Forry started showing strangers around their house every Saturday.

The assortment which caught Harryhausen's eye was merely the seed of what would grow into a great oak -- nay, a forest. Ackerman's repository of movie stills, props and masks, books, posters, paintings and other items developed into what has been called the largest personal collection of genre memorabilia in the world. An estimated 300,000 artifacts once filled Forry's "Ackermansion," the 18-room Los Feliz home he shared with his "life companion," wife Wendayne, the college professor and translator of French and German science fiction novels who wondered why, in 1951, Forry started showing strangers around their house every Saturday.

Whatever he was thinking, there was no going back for Ackerman, who proudly welcomed thousands of pilgrims to his own private Mecca and showed them Bela Lugosi's Dracula cape and ring, Spock's pointy ears from Star Trek, and Harryhausen's miniature Capitol Dome, as well as pieces from King Kong, Phantom of the Opera, Invaders from Mars, and Raiders of the Lost Ark. Visitors were astonished at the invitation to touch a signed first edition of Bram Stoker's Dracula (which Forry also had signed by Lugosi, Christopher Lee and Frank Langella). There even were odes to Ackerman's favorite film, Metropolis, including the famous Maria robot and director Fritz Lang's monocle. But Forry never forgot where it all started, and happily drew from his intimidating bookshelves that immortal issue of Amazing Stories.

(And how's this for coming full circle: in 1953, "Number One Fan" Ackerman won the prestigious Hugo Award, which was named for Amazing Stories publisher Gernsback.)

After a while, Forry didn't even need to seek out new treasures; they came to him directly from the filmmakers themselves. Director Steven Spielberg autographed a Close Encounters of the Third Kind poster for Ackerman, including the endearment, "A generation of fantasy lovers thank you for raising us so well." Indeed Spielberg was one of many -- such as Stephen King, Joe Dante, George Lucas, Billy Bob Thornton, Gene Simmons and Tim Burton -- who grew up on Uncle Forry's Famous Monsters of Filmland.

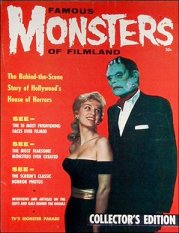

Launched in February 1958, Famous Monsters of Filmland (above right) was the first serious magazine devoted to horror and science fiction cinema. It featured interviews with writers, directors, and genre stars such as Lugosi, Boris Karloff and Vincent Price. It also was among the first publications to bring makeup and special effects technicians into the limelight. Famous Monsters may have looked cheap, with its black and white content on low-quality paper, but Ackerman's experience as a book editor (for the likes of Isaac Asimov) and prolific writer of stories and articles compensated nicely. Plus Forry was able to draw from his incomparable photo archive to illustrate each issue. And of course there was his infectious love of the material and his sense of humor: features were titled with characteristic puns such as "The Printed Weird" and "Fang Mail."

"He put a lot of his personality into the magazine," Fangoria's Tony Timpone told The LA Times in 2002.

Ironically, the work of a fan developed its own fandom and turned Uncle Forry into a geek's rock star. Over three days at a New York City monster movie convention, Ackerman once scrawled his autograph for 10,000 acolytes.

But he didn't rest on those laurels. His output included, among other things, the comic book superheroine Vampirella and the first published lesbian science fiction story, "World of Loneliness," for which he was named an Honorary Lesbian by the lesbian rights group Daughters of Bilitis. He acted or cameoed in a slew of films, mostly shoestring-budget fare such as Amazon Women on the Moon. But there was the occasional classic like Dante's The Howling and the Michael Jackson video Thriller.

There also was that other thing -- the famous term many have attributed to Ackerman (others have credited Heinlein).

"My wife and I were listening to the radio, and when someone said 'hi-fi' the word 'sci-fi' hit me," Forry told The Times of that fateful day in 1954.

The stories aren't all so rosy, especially in later years. Famous Monsters, which had folded in 1983, was resurrected -- with Forry's blessing and participation -- a decade later by publisher Ray Ferry. However, a falling out led to years of litigation that depleted Ackerman's finances. Wendayne didn't see how long it ultimately dragged out: she died in 1990 and was buried in Glendale's Forest Lawn Cemetery under the marker "Beloved Wife of Mr. Science Fiction."

Health problems and the legal battle led Ackerman in 2002 to move from the Ackermansion into a bungalow he called the "Acker Mini-Mansion," which housed the 100 or so relics he retained after selling the bulk of his collection.

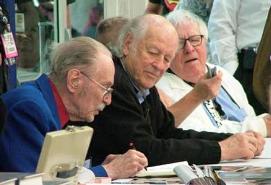

More importantly, he retained his fans and friends until the end. His great discovery, Bradbury, saw him as late as the '08 San Diego Comic-Con (seen here with Harryhausen). Even when battling an infection around Halloween, Uncle Forry outlived predictions: on November 6th, Locus.com, the British Fantasy Society and Wikipedia all announced his death. Retractions followed.

On his MySpace page, where his hometown is listed as "Mars," Ackerman contemplated his ultimate fate. "It would be nice to look forward to going to a Great Sci-Fi Convention in the Sky when I expire ...but... I, like Isaac Asimov and other thinkers I admire, don't expect to wake up in some spirit realm of an afterlife."

Whether or not the secular humanist, described by the Horror Hall of Fame as "The Hugh Hefner of Horror," finds anything on the other side of death, he has found immortality on this side. He left behind no children of his own but instead a lot of nieces and nephews. Ironically (or perhaps appropriately), after all his impressive accomplishments, Forrest J Ackerman can be fairly neatly summed up by The Scifipedia's definition of him: "American fan."

[Original report by DENNIS MCLELLAN. Thanks to the NJ Star-Ledger's STEPHEN WHITTY, Sci Fi Wire's DON WEBB and JOHN JOSEPH ADAMS, Time's RICHARD CORLISS, and The Washington Post.]